| Added | Wed, 22/12/2021 |

| Источники | |

| Дата публикации | Tue, 08/11/2016

|

| Версии |

"It wasn't like that at all!". How often do people encounter such an answer when discussing stories from their distant childhood or from their past with relatives? Memory turns out to be an unreliable source of information, and even in some cases we not only forget some important elements, but "think out" something new. This kind of memory error is called false memories.

Human memory is not analogous to a computer or recorded video: every time a person remembers an element of information, a reconstruction of this event takes place in the brain, which in some cases entails changes. But what is going on in our brain that causes memory to change so much?

A group of scientists from Duke University in the USA tried to answer this question by literally forcing the participants of the experiment to remember what actually did not happen. The results of the study are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Two dozen people were invited to the MRI lab, who had to watch 70 short videos - like at a festival of advertising or short films. The day after that, they watched the video again, but now half of the video clips were interrupted at the climax without warning.

For the participants, such an event became a surprise, and any element of surprise is encoded in the brain by the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, acetylcholine and norepinephrine, helping to capture the event in more detail. On the third day, the subjects were interviewed to find out how much detail they remembered the plot of the video. It turned out that most of them thought up the content of the interrupted videos they watched. They formed a false memory of the clip they watched.

The researchers paid attention to what happens in the brain at the moment when people encounter an unexpected event - an element of surprise, for example, with the interruption of a video at a key moment. They focused on studying such a structure as the hippocampus, a region in the temporal lobe of the brain responsible for transferring information from short—term to long-term memory.

At the moment when the participants watched the video to the end, the activity of the hippocampus was stable. But after interrupting the video in the middle, the stability of activity patterns was disrupted, it was like switching to a "different mode" that allows updating the content of the stored information.

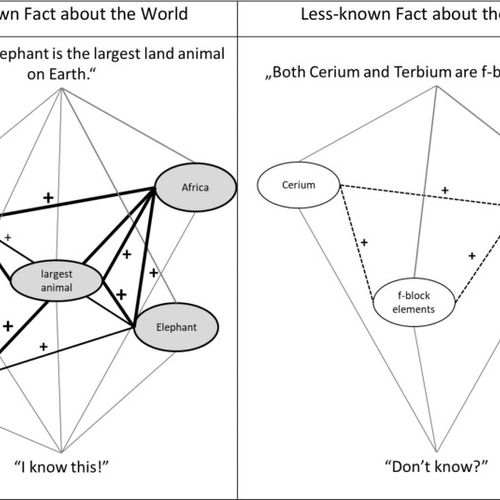

The more unstable the interruption pattern was, the more likely people were to create false memories. Most often they were created on the principle of similarity, for example semantic proximity: fragments in one video about sports were replaced by episodes from another.

The results showed that the method allows to distinguish false memories from real ones with high reliability. In particular, the examined subjects had stable false memories in 30.4 percent of cases: they perceived an induced memory (for example, a balloon ride) as a real thing that happened to them, they could describe it in detail and compare it with anything. Another 23 percent of participants accepted false memories to some extent and generally also believed they had occurred.

According to scientists, the data obtained indicate the need for further study of the phenomenon. In addition, such a prevalence of false memories casts doubt on the established practice in a number of industries, including the practice of psychotherapy, interrogation of witnesses and suspects, medicine. Especially noteworthy in this context is the possibility of inducing false memories by the mass media (mass media) due to the repetition of various (distorted) facts — such memories can be collective.

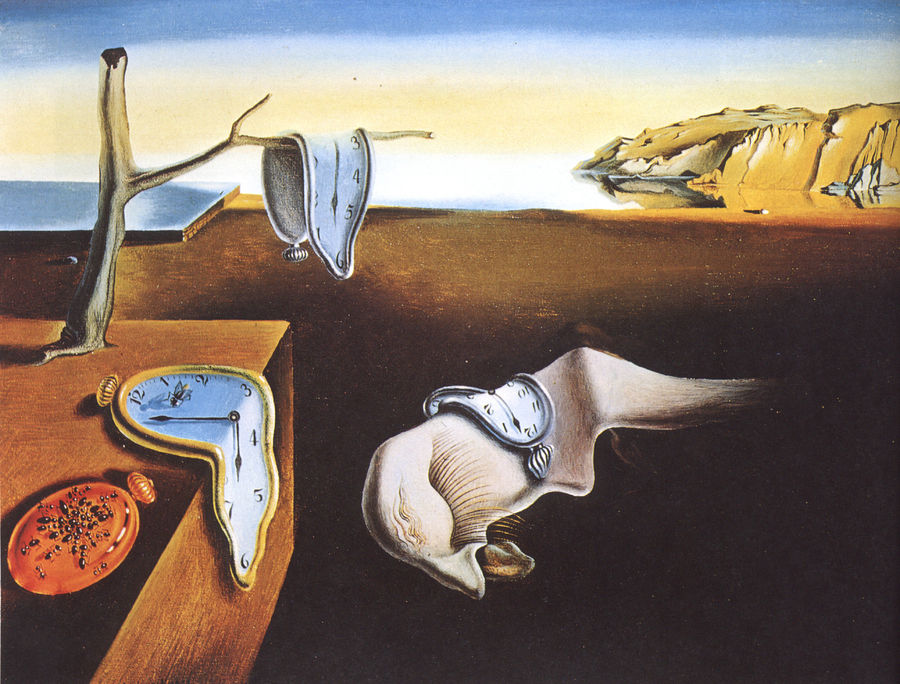

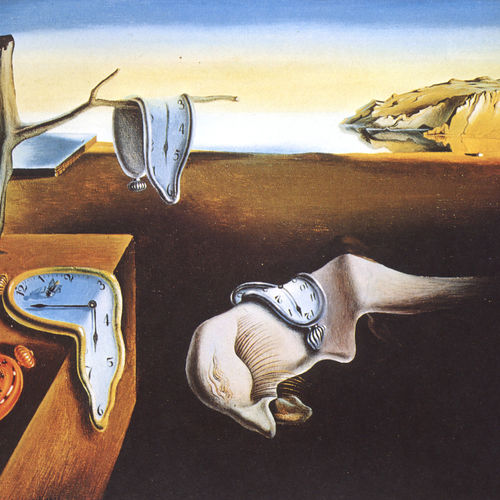

Illustrative image

Salvador Dali "The Permanence of Memory". 1931

Spanish La persistencia de la memoria

Oil on canvas. 24 × 33 cm Museum of Modern Art, New York

Новости со схожими версиями

Log in or register to post comments