| Added | Sat, 25/05/2024 |

| Источники | |

| Дата публикации | Sat, 25/05/2024

|

| Версии |

In the information age, when we are literally drowning in the flow of news, blogs and social media, it is important to understand how our brain processes all this mass of data. A new study by German scientists sheds light on the mechanisms that affect our perception of truth and memory.

The "truth effect" and its consequences

It has long been known that the "truth effect" is a cognitive distortion in which we tend to believe information that we encounter repeatedly, regardless of its actual accuracy. Our brain processes repetitive information more smoothly, and this ease of perception is interpreted by us as a sign of truth.

The results of a recent study published in the journal Cognition show that this effect may be even stronger than previously thought. Scientists have called this phenomenon the "illusion of knowledge effect."

In a series of experiments involving almost 800 people conducted by Dr. Felix Speckmann and Dr. Christian Unkelbach from the University of Cologne, it was found that participants tended to believe that they knew repetitive information in advance, even if this was not the case. This effect was observed even in the case of false statements.

The illusion of knowledge

One experiment showed that participants were more likely to rate repeated statements as "known" to them before, even if they were false.

The researchers also examined whether asking participants to identify the source of their knowledge could affect the illusion of prior knowledge. It turned out that even when the participants were asked to name the source, they rarely corrected their initial judgment, demonstrating the stability of the illusion of knowledge.

Interestingly, participants often attributed their "previous knowledge" to trustworthy sources, even if the original source of information was unreliable. This tendency to fabricate reliable sources highlights the power of repetition in shaping our beliefs.

Forgetting and misinformation

The study also sheds light on how forgetting can affect our perception of the truth. Scientists have found that when people come across information from unreliable sources, they may initially understand that they cannot trust it. However, over time, they forget the original source, and if they come across this information again, they tend to rate it as more truthful.

"The forgetting effect, combined with the truth effect, can lead people to believe statements that were initially identified as unreliable," the researchers write.

The Mandela Effect

The results of the study are also relevant to such a phenomenon as the "Mandela effect". This effect, named by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome, describes a phenomenon in which large groups of people remember an event differently than it happened, or recall events that never happened.

A classic example of the Mandela effect is the widespread false belief that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s. In fact, he was released and became president of South Africa, passing away in 2013. Scientists suggest that the Mandela effect may be partially explained by the repetition of false information or incorrect association of information sources.

The results of the study have important implications for combating disinformation in the Internet age. They show that simply exposing false information may not be enough, as over time people may forget the original source and believe in this information again when confronted with it again.

Scientists emphasize the need to develop critical thinking and media literacy so that people can better assess the reliability of information and resist the influence of the effect of truth and the illusion of knowledge.

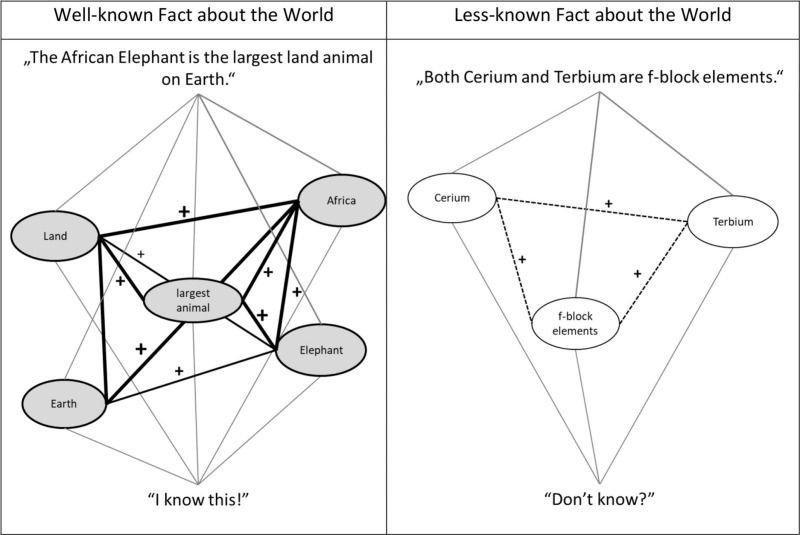

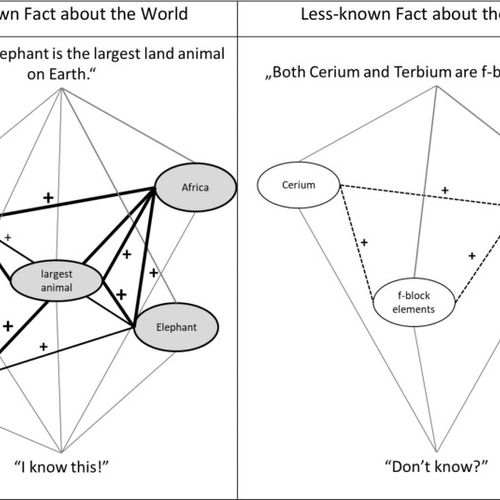

An illustration of how people judge whether they know information.

The panels illustrate localized reference networks for well-known and lesser-known facts about the world. Light gray lines indicate incoming information. The gray circles indicate the references that exist in the memory, which give meaning to the statement. White circles indicate information that does not have links in memory. Solid lines indicate existing links between links. Dotted lines indicate links triggered by the presentation. The "+" sign indicates a coherent connection, and the "-" sign indicates an incoherent connection (not shown). The thickness of the line indicates the strength of the connection.

Новости со схожими версиями

Log in or register to post comments