| Added | Tue, 28/12/2021 |

| Источники | |

| Дата публикации | Tue, 28/12/2021

|

| Версии |

For all its dazzling complexity, the human brain can produce amazing phenomena. For some, this means hallucinations of tiny people flashing before their eyes.

Hallucinations associated with shrunken people can be funny or frightening, depending on who you ask, and there are quite a few stories in the scientific literature about these "micropsychic" or "lilliputian" visions. In fact, only a few researchers have tried to figure out what is behind these strange experiences at all.

What are Lilliputian hallucinations?

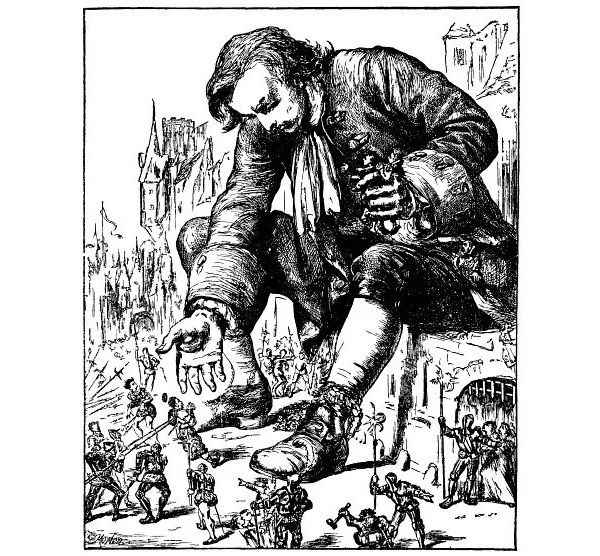

In the early 1900s, the French psychiatrist Raoul Leroy became interested in observations of human figures comparable to the tiny inhabitants of Lilliput from Jonathan Swift's famous novel Gulliver's Travels, written in 1726. For him, it was a puzzle of the mind, requiring a scientific explanation.

"Such hallucinations exist outside of any micropsia, while the patient has a normal idea of the size of the objects that surround him, micropsia affects only the hallucination," Leroy wrote in the introduction to one particular case. "Sometimes they occur on their own, sometimes they are accompanied by other psychosensory disorders."

The small handful of cases considered by Leroy were surprisingly diverse, although in general, as he noted, the visions were colorfully dressed, very mobile and mostly friendly. Sometimes individual figures were present in the visions, although most patients reported that they appeared in groups, interacted with the material world as if they were really present in it, climbed on chairs, squeezed under doors and obeyed gravity.

Not all experiences were so benign. In one of the studies, Leroy told about a 50-year-old woman with chronic alcoholism who claimed to have seen two men "as tall as a finger", dressed in blue clothes and smoking a pipe, sitting high on a telegraph wire. During the observation, the patient claimed that she heard a voice threatening to kill her, after which the vision disappeared and the patient ran away.

"In my previous message to the Medico-Mental Society, I said that these hallucinations had a rather pleasant character, the patient looked at them with the same surprise as with pleasure," Leroy noted. "Here, as in the case of MM. Bourneville and Brecon [two other cases], the phenomenon caused a feeling of fear."

What we might consider simple nonsense, Leroy interpreted as possible symptoms of mental illness worthy of classification, so that doctors could come up with better ways to diagnose and even treat.

Under the influence of Leroy's work, several psychologists have tried to explain this phenomenon. Basically, they were limited to untested hypotheses related to the mysterious work of the midbrain or Freudian regression.

Despite such early interest, Lilliputian hallucinations are not a criterion for any disease in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems. It seems like it's almost a random brain quirk.

Charles Bonnet syndrome is one notable exception: This is a rare disease in which hallucinations occur as a result of vision loss. Although these hallucinations do not always take the form of tiny people (they can be flashes of light, geometric shapes or even just lines), they can also be Lilliputian.

A study conducted in 2021 on a sample of volunteers with active Charles Bonnet syndrome showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the frequency and obsession of hallucinations increased, most likely due to loneliness in isolation cells. In some cases, the size of the Lilliputian hallucinations increased to human size.

What do we know about Lilliputian hallucinations today?

Despite Leroy's historical work and progress in understanding many mental states, surprisingly little is known about why some people's brains create visions of tiny people.

Recently, medical historian of Leiden University and researcher of psychotic disorders Jan Dirk Blom decided to change this situation by undertaking a thorough search for reports of cases of Lilliputian hallucinations in modern medical archives.

After a thorough search, Blom managed to find only 26 works about Lilliputian hallucinations that can be considered relevant. Of these, only 24 contain original case descriptions.

"In the 1980s and 1990s, new cases were published extremely rarely, and the question of the original source of Lilliputian hallucinations has sunk into oblivion," Blom writes in his study published in the journal Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews in 2021. "Despite some renewed interest in this phenomenon in the last two decades, this situation has hardly changed."

Turning to more historical and less clinical sources, including book chapters and medical dissertations, Blom eventually compiled a catalog of 226 unique cases for comparison and comparison.

Their experience and background were very different, equally men and women, the age of the oldest was 90 years old, and the youngest was only four years old. But there were many similarities.

Most people reported hallucinations dressed in bright, colorful clothes. These were not vague shadows hiding in the corner of the eye, but a bright circus with clowns, harlequins or even jumping soldiers. Only a small number of cases reported visions in "gloomy" or gloomy shades of gray or brown.

Almost all the figures were unfamiliar, and only in a few cases there were familiar faces, including cases of autoscopy (seeing oneself in a tiny form). In a fifth of all cases, the visions were accompanied by auditory hallucinations, often muffled or with a high timbre.

People were not the only objects of observation. In almost a third of cases, patients claimed to have seen animals, such as small bears or small horses pulling small carts.

Of particular note is the fact that 97 percent of the cases were projective, appearing in three dimensions and interacting with real-world physics. The remaining cases were presented as two-dimensional projections on the surface or moved when the observer's head moved.

It is also interesting to note that almost half of the cases left a negative impression, fear or a feeling of anxiety. In contrast to Leroy's assessment made at the time, only a third of these cases were reassured or entertained by their experiences. In one case, a depressed patient claimed that visions were his only joy.

Referring to the reports on clinical diagnoses, Blom identified 10 separate groups, among which the most noticeable were mental disorders, alcohol or drug intoxication and lesions of the central nervous system.

It is not difficult to imagine that the visual system of the brain is involved in the process; MRI studies of patients with Charles Bonnet syndrome confirm this. But something more concrete must be happening, and detailed studies at the neurological level are not yet available.

Blom suggests that the loss of peripheral sensory input may mean that the parts of the brain normally involved in information processing go beyond the task, piecing together what little stimuli they can find to weave a fantastic scene out of the crowd and color.

The fact that this is a common experience for people with Charles Bonnet syndrome, and people with conditions such as Parkinson's disease sometimes report hallucinations at dusk, seems to add weight to this hypothesis.

Other models can also explain these visions, perhaps this is a way of "invading sleep", when usually suppressed images bubbling under the blanket of everyday perception break out, mixing with reality in a strange way. Or perhaps it's a mixture of neurological phenomena, stealing inspiration from memories, or rethinking ordinary physical sensations, such as the flies in our eyes that we all see twitching in the corner of our vision.

Considering that tiny human figures occupy an important place in folklore around the world in the form of mischievous elves and playful imps, scary demons or wise old gnomes, we seem to be more interested in reports as stories than as quirks of neurology.

Perhaps someday this will change, and our stories about the little inhabitants of our environment will tell us as much about the work of our brain as about our cultural heritage.

Новости со схожими версиями

Log in or register to post comments