| Added | Fri, 27/05/2022 |

| Источники | |

| Дата публикации | Fri, 27/05/2022

|

| Версии |

As the Earth orbits the Sun, it passes through dust and debris left by comets and asteroids. These fragments generate meteor showers - one of the most amazing sights in nature.

Most meteor showers are predictable, they are repeated annually when the Earth passes through a certain trail of debris.

However, sometimes the Earth passes through a particularly narrow and dense accumulation of debris. This leads to a meteor storm, as a result of which thousands of shooting stars sweep across the sky every hour.

A small stream called Tau-Herculides may cause a meteor storm for observers in North and South America next week. But although some sites promise "the most powerful meteor storm in the last few generations," astronomers are a little more cautious.

Introducing Comet SW3

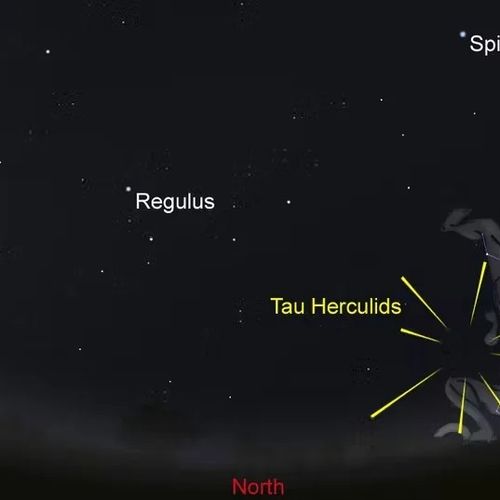

The story begins with a comet called 73P/Schwassman-Wachman 3 (abbreviated SW3). First spotted in 1930, it is responsible for a faint meteor shower called Tau Herculides, which currently appears to be coming from a point located about ten degrees from the bright star Arcturus.

In 1995, comet SW3 suddenly and unexpectedly became brighter. Several outbreaks have been observed for several months. The comet catastrophically shattered, throwing out a huge amount of dust, gas and debris.

By 2006 (after two orbits), comet SW3 had broken up even more, into several bright fragments, accompanied by many smaller pieces.

Is the Earth on the collision course?

This year, the Earth will cross the orbit of comet SW3 at the end of May. Detailed computer simulations show that the debris is spreading along the comet's orbit like huge thin tentacles in space.

Did the debris fly far enough to collide with the Ground? It depends on how much debris was ejected in 1995 and how quickly these fragments flew apart during the decay of the comet. But the dust particles and debris are so small that we can't see them until we collide with them. How can we understand what might happen next week?

Can history repeat itself?

Our current understanding of meteor showers began 150 years ago with an event very similar to the history of SW3.

A comet called 3D/Biela was discovered in 1772. It was a short-period comet, like SW3, returning every 6.6 years.

In 1846, the comet began to behave strangely. Observers saw that her head split into two parts, and some described an "arch of cometary matter" between the parts.

During the comet's next return, in 1852, both fragments clearly separated, and the brightness of both fluctuated unpredictably.

The comet was never seen again. But at the end of November 1872, an unexpected meteor storm swept across the northern sky, stunning observers with a speed of more than 3,000 meteors per hour.

The meteor storm occurred when the Earth crossed the orbit of 3D/Biela: it was located where the comet itself should have been two months earlier. The second storm, weaker than the first, occurred in 1885, when the Earth again collided with the remains of a comet.

3D/Biela disintegrated into fragments, but the two large meteor storms that it produced served as a worthy guide.

A dying comet, disintegrating before our eyes, and a meteor shower associated with it, usually barely noticeable against the background of noise. Will the story of comet SW3 repeat itself?

What does this mean for Tau Herculida?

The main difference between the events of 1872 and the Tau-Herculides of this year is reduced to the time when the Earth crosses cometary orbits. In 1872, the Earth crossed the orbit of Bijela a few months after the comet was supposed to appear, passing through material lagging behind where the comet was supposed to be.

In contrast, the Earth's encounter with the SW3 debris stream next week will occur several months before the comet reaches the intersection point. Thus, for a meteor storm to occur, the debris had to spread before the comet.

Can the debris fly far enough to collide with the Ground? Some models suggest that we will see a strong show from the meteor shower, others say that the debris will fall very close.

Don't count meteors before they flare up!

Whatever happens, observations of the flow next week will greatly improve our understanding of how comet fragmentation occurs.

Calculations show that the Earth will cross the SW3 orbit at about 15 hours on May 31 (AEST). If the debris passes far enough ahead for the Earth to collide with them, then an outbreak from Tau Herculides is quite likely, but it will last only an hour or two.

From Australia, the show (if there is one) will end before dark to see what is happening.

However, observers in the Americas will have the opportunity to observe what is happening.

Most likely, they will see a moderate manifestation of slow-moving meteors, rather than a huge storm. This will be a great result, but it may be a little disappointing.

However, there is a chance that the downpour will show a really impressive sight. Just in case, astronomers go on a trip around the world.

What about the Australian observers?

There is also a small chance that the activity will last longer than expected, or even come a little later. Even if you are in Australia, it's worth looking up on the evening of May 31 - suddenly you will be able to see a fragment of a dying comet!

The 1995 debris flow is just one of many deposited by the comet in recent decades.

In the early morning of May 31, around 4 a.m. (AEST), the Earth will cross the debris of a comet formed during the passage of a comet around the Sun in 1892. Later in the evening, around 20 hours on May 31 (AEST), the Earth will cross the debris deposited by the comet in 1897.

However, the debris from these visits will dissipate over time, and therefore we expect that only a few meteors from these streams will decorate the sky. But, as always, we can be wrong - the only way to find out is to go out and take a look! Discussion

Jonty Horner, Professor (Astrophysics) at the University of Southern Queensland and Tanya Hill, Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Melbourne and Senior Curator (Astronomy) at the Victoria Museum.

Новости со схожими версиями

Log in or register to post comments